At this bizarre

conjuncture maybe I should be saying, as Samuel Beckett said to Edna O’Brien

when she asked if he was writing anything: “and what use would it be, anyhow?” What

use, indeed, if he was on his deathbed and if any lines he might pen at that

point could be his last, going nowhere, leading to the completion of no

meaningful work?

In my case, I am

composing, but not in any sense I might have been at any time before.

The circumstances of the

last year have precluded a proper immersion in creative work. I have remained

productive, first of all in order to fulfil existing commitments, such as LoA

(Sage Gateshead, September 2018) and A Northumbrian Anthem (August

2018). Composing them was difficult, not least in a logistical sense, with no

music keyboard or even of an alphanumeric keypad, which until then had seemed

essential for music notation input. But the effort also helped to sustain me when

things were hard, and to focus on something positive.

After that, other

pressing challenges - not of a musical kind - absorbed my energies. But it was not possible to defer

composing for very long. Writing music was and is essential to who I am, and to

abandon it for any length of time would endanger my sense of self.

After some struggle, I found a compromise: I could go on composing by writing shorter, less

demanding pieces in the crevices of time and strength the situation allowed. And, since we

don’t know how long I will be in a position to continue to write music, thoughts have to turn to debts, that is, pieces I had been feeling for some time that

there was a moral imperative to write. That was the case of the choral piece A

Don Franklin (October 2018), a homage to Franklin Anaya Arze which is

intended to rectify an imbalance left by the oft-performed (too oft, I wonder?)

Himno al Instituto Laredo (1979).

There are also what

could be termed aesthetic debts to repay. I cannot forget the mission statement

I came up with in a late-night conversation with my eldest sister, Beba, back

in 1970 or 1971. I was twelve or thirteen then, and was in the process of discovering

the classical repertoire after a few years spent playing folk and traditional

music. I told my sister that my ambition was to absorb the technique of the

classical masters to put it at the service of a new folk music. I said words to

the effect that my music would have to be a conversation between the two

traditions. Mind you, I had not heard much twentieth-century music at that

point.

Naïve and juvenile perhaps,

but that manifesto was sincere, and in some important ways I have adhered to it.

There is no denying that my immersion in classical music became total for many

years – as it had to be, given how much there was to learn. But it is equally

undeniable that the “classical” music I wrote throughout the 1970s in Bolivia (say,

Rapsodia, or Misa de Corpus Christi) was, recognisably, also folk

music. In the following decades I wrote music which, to British and USA

audiences, might sound “very Bolivian” (or, for those who know less, “very Latin”),

whereas for Bolivian audiences it would sound “very classical” (or, for those

who know less, “very contemporary”). Those are typical reactions from audiences.

Each constituency would be aware of the otherness. This could mean that, as in today’s

BBC bias argument (“if all sides are unhappy they must be getting it right”), I

have been hitting the right spot. Or it could mean that, whatever the

demographic of my audience, they find my music alien.

Do we want to be defined

in terms of our otherness? I am sure I am not the first composer to ask this

question. Of course, the absolute majority of creative artists would like to be

perceived as original. But do we want to be perceived as other? As alien,

even? What would the opposite of that be? What would it be like to be

recognised as familiar, kindred, relevant, congenial? How would that music

sound? Unappealing thought, especially if we think of the traits such music

would need to have to sound familiar, kindred, relevant and congenial to

listeners – present or future – of today’s contemporary music.

The thought is more appealing

to me if I imagine a Bolivian listener – Latin American, even, and not

necessarily one from the thinly-populated spheres of contemporary music

audiences – recognising what I write as familiar, kindred, relevant or

congenial. What would that music have to sound like? Have my decades of working

immersion in classical music first, and then in contemporary classical music,

distanced me beyond recall from that listener? To the first of these two

questions I have been addressing my thoughts for quite some time. To the second,

I do not have to think to answer: the answer is no.

I am not, I cannot be too

far removed from a Bolivian, or Latin American, who is sufficiently interested

in music to listen to something I have written. I would go further: I cannot be

too far removed from any listener from any origin who happens to cross paths

with my work. Not if by “being far removed” we mean that my music leaves them

behind by virtue of being too rarefied. The reverse is more likely to be the

case, and I am sure it has happened already. In the lofty echelons of post-serial

music practice and thinking, I am pretty sure my music must have been dismissed

many times as “post-tonal” or “emotive” or other such dirty words from the

avant-garde lexicon – not that I have heard them; I would be very unlikely to,

since such circles are oh so universally polite. These high spheres are prone

to exclusivism, and my heart does not ache unduly at being excluded from them,

other than to regret the denial of access to some superb performers and

performance opportunities. It must be said, however, that I suspect that the

reasons for the exclusion are not musical, or not always.

If those stratospheric practitioners

and thinkers have shown mistrust towards my serious works – the quartets, the orchestral

pieces, Approaching Melmoth – perhaps I ought to shudder at what they would

say about my efforts of the last year. But I am past shuddering. I am too busy facing

real dangers in other parts of my life. Let the lofties sniff, let them sneeze,

let them choke if they have to. I have a job to do, and not many months to do

it.

To what extent national

identity can be part of a recipe for originality is debatable. I have no

intention to use mine in that way, and am under no illusion that being Bolivian

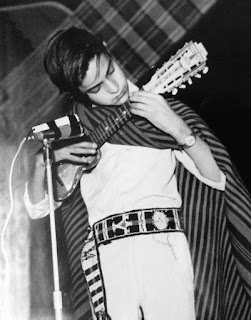

will save me from oblivion. All I know is that I started off as a folkie; a

premature one, maybe, but an earnest one; I was serious about what I did back

in 1969 and 1970. Are you too young to be serious about what you do at that

age? Well, I wasn’t (too young), and I was (serious about what I did).

I started off as a

folkie, I was saying, and then life put other exciting music in my way. I loved

this even more, but I also saw the need for consistency, for loyalty. So that

is what I came up with – the formula I confided to my sister. To save you scrolling

up, it was: “my music [will] have to be a conversation between the two

traditions [folk and classical].

I had hoped to have

plenty of time to consider this challenge in my maturity, but I may be being overtaken

by events. In an implicit sense all my work has been that: a dialogue of two

traditions – at least two. But a conversation in an explicit sense in which two

characters are put centre-stage and are seen to converse, distinctly enough for

any listener to distinguish between them, including that hypothetical listener who is not

used to contemporary music or even to classical music. Have I done that before?

I hadn’t, but I have now. This is the first attempt. Ideally it will be the

first of a series. Let us see.

The title should be

self-explanatory as to who the characters in the conversation are. The title is

also an affectionate homage to Heitor Villa-Lobos, who did something comparable.

He did it more subtly – but hey, mine is only the first of a series. Or so I

hope.

For those unfamiliar with the genre, the structure and rhythm correspond to taquirari, the emblematic genre from the eastern lowlands where I grew up. Is this a pastiche? Emphatically not. This is my mother tongue.

Until Trío Apolo of

Cochabamba have the chance to record it, all we have is the dreaded computer

simulation.